I met Emily in the fall of 1967, during the anti-war march on the Pentagon. That protest—tens of thousands strong—was a rupture. D.C. felt electric and volatile, like the air before a lightning strike. The war was surging, and so was the resistance. Students, clergy, veterans, poets, and provocateurs collided, not always in harmony. The movement was splintering: some preached peace, others demanded revolution. Everyone wanted change, but no one agreed on its shape.

Several years before this, I started writing letters to my draft board. Lyndon B. Johnson was still president, Nixon waiting in the wings. The letters weren’t meant for Johnson, but I imagined him reading them anyway—grimacing, maybe, before tossing them aside. The draft board replied a few times, reminding me I was deferred under 3-A college status. Eventually, they recalculated me as 1-A. Combat-ready. And I welcomed it. You can’t refuse what hasn’t been offered. I was done hiding behind loopholes.

I’ve never had patience for those who ran to Canada, claimed bone spurs, or found clever ways to dodge the draft. If others were saying yes by dying, I could damn well risk my freedom to say no—with my body, not just my words. That was the point. Resistance isn’t clean. It’s not comfortable. It’s not supposed to be.

I first met a friend of Emily’s who invited me to speak at George Washington University about my involvement. Emily was there. Back of the room. Silent. Motionless. She claimed a corner as if it were a refuge. Twenty, maybe twenty-five people in a vast lecture hall. Most clustered together, ready to pounce. She stood apart. Her small frame held a quiet strength.

As I spoke, the questions came hard—verbal rotten tomatoes, launched like missiles. Who was I to think I could end a war? Why did I care? I was safe. I was free. But I kept looking toward her. She hadn’t said a word, yet

I felt held by her silence.

And then she spoke. Softly. Simply. Powerfully.

“Wouldn’t you want them to do the same for you,” she said, “if it were your children being napalmed?”

That sentence still echoes. In 1967, napalm wasn’t theoretical—it was the image on the evening news, the smell in the back of our throats. Her words cut through the noise like truth often does. Amid the shouting, she was the still point.

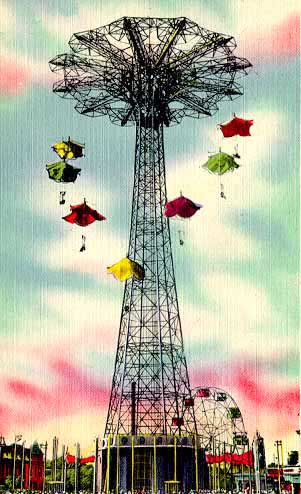

We met again later that year at another protest in New York City. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was speaking at Riverside Church. That speech—his first significant break with the Johnson administration—was a thunderclap. He called the U.S. “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” It cost him allies, but it galvanized many of us. Emily and I never saw him speak. Instead, we ended up at Coney Island—my first and only time there.

She convinced me to ride the Parachute Jump, a steel skeleton of a tower that looked like it had been designed by someone with a grudge against gravity. Two-person canvas seat. Lifted 250 feet into the sky. Dropped like a stone. Caught, eventually, by a parachute that felt more like a suggestion than a guarantee.

She said it would be fun. I said yes, mostly to impress her. It was not fun. It was terrifying. But she laughed, hugged me, and called me brave. Said it was one of the best experiences of her life. I didn’t understand how she could enjoy it. But I was falling for her faster than that drop from the tower. Before we parted, she told me: if I ever needed a safe place, she had land in West Virginia.

The Pentagon was thunder. Riverside was lightning. But Emily—Emily was shelter. In the roar of fractured movements and rising resistance, she offered stillness. Her words didn’t shout; they landed like balm. Even that wild ride at Coney Island, terrifying as it was, became a metaphor: the world drops you, but sometimes you’re caught—not by canvas or steel, but by someone who sees you.

Before we parted, she offered land in West Virginia—a place untouched by sirens or slogans. A sanctuary. And I began to wonder: maybe the revolution wasn’t just in the streets. Perhaps it was also in the quiet spaces we build with each other.

After more than fifty years, I’ve learned that quiet doesn’t always live in geography. Sometimes it’s tucked into memory, into rituals that outlast the hands that once performed them. And sometimes, it’s the comfort and warmth of remembering the people who held me when the world did not.

Maybe that’s the revolution too—not just in the streets, but in the stillness we carry forward.

And the real question is this: when the world lets you down, who catches you?

A mountain. A mouse. A friend on a grimy sidewalk. Sometimes, that’s enough.

Leave a comment