My father died in December 1967. Cancer. A slow, cruel thief that stole him piece by piece until all that remained was silence. I was twenty-one, and the world was already loud with war.

The night before my induction, sleep refused to visit. I lay in bed, staring at the ceiling like it owed me answers. My heart was a metronome gone rogue—too fast, too loud, too erratic. I tried counting breaths, replaying old football games, pretending I was anywhere but here. But dread crept under the door and settled in my bones. I wasn’t afraid of dying. I was scared of disappearing—of becoming a number, a uniform, a cog in a machine I didn’t believe in.

The draft lottery, America’s twisted game show of fate, didn’t begin until December 1, 1969. But in 1964, the draft was still operating under a local board system, where deferments (for college, hardship, etc.) and classifications were manually reviewed. In 1964, when I was eighteen, I burned my college deferment draft card, thinking I was making a statement. At the same time, I began writing letters to the President of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson, expressing my opposition to the war and to my draft board on Staten Island, requesting reclassification to 1-A. You can’t refuse what you haven’t been offered. And I was tired of, if not exactly hiding behind loopholes, then at least I was tired of accepting them.

I was writing the first line of a much longer story. By ’69, they changed my deferment and reclassified me 1A—fit for service, next in line to toe the line, or not. I was on the verge of something, though I couldn’t name it. It had taken me 5 years between business schools and seminaries to get here. I think of that time as going from the gridiron to leg irons.

And then the morning came. I was up and gone by 6 am. I wasn’t sleeping anyway, leaving a note for my mother, telling her I had gone to visit friends. I wondered how long I really would be gone. I took the bus to the Staten Island Ferry, which crosses the Hudson River. Whitehall Station was about two blocks from the Ferry terminal. It must have been the longest two blocks I have ever walked, and the slowest. I was in no hurry. Just writing about that morning, I can still feel that god-awful, sinking, sick feeling in my stomach; I can’t do this.

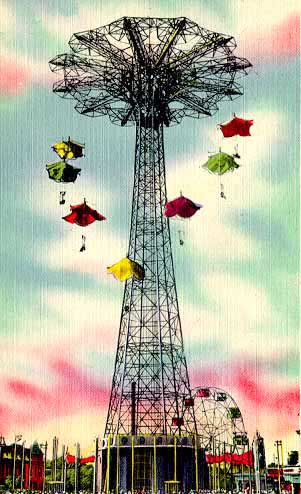

You’ve heard of the fight-or-flight response. Mine was freeze and fall. No exit. Just a heart pounding like a drumline on speed, and a cliff edge I couldn’t see the bottom of. I was about to dive into the dark. Compared to this, the Coney Island Parachute Jump was a kiddie ride.

Whitehall Station sat in lower Manhattan like a bureaucratic bunker—the Army’s induction center where boys became soldiers, or tried not to. It shut down on May 18, 1972, two days before my birthday, while I was sitting in the Danbury Federal Correctional Institution, partly because I wanted it torn down and had done my best to see that happen.

As I walked up the last few steps to enter the building, I found Mr. Harold Jones waiting outside Whitehall Station. My eighth-grade science teacher, yes—but more than that, over my high school years, and not really having anyone else to talk to who seemed to understand what I was feeling, Mr. Jones became my confidant and my co-conspirator in resistance. He had made science feel like storytelling, helped along by a fictional mouse named Archibald MacLeish who lived in his coat closet. Archibald, named after the poet and war veteran, wore a French beret, a red bandana, and carried a cane. No one ever saw him, but I did. I still do. He walks proudly, head high, like he knows something the rest of us don’t. We said very little to each other that morning. I thank him for being there. He said something about me staying me, it was something to be proud of.

The induction ceremony began. The room smelled of sweat and floor wax. The air was thick with the breath of boys pretending not to shake. The recruiter’s voice was flat, rehearsed, like he’d stopped listening after the first hundred times. Repeat after me, he began.

“I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution…”

He barked it out. Repeat? Hell, I could barely breathe. I needed time. I needed space. I needed something other than this.

“…that I will bear true faith…”

And suddenly I wasn’t in Whitehall anymore. I was back on the football field, hearing my coach yell, “Go in hell-bent for leather, Little Sandy!” My dad was Big Sandy. The coach used that nickname to rile me up. Hell-bent for leather. Hell-bent for leather. My heart picked up the chant, louder and louder, until it drowned out everything else.

Then came the words: “Step forward.”

I sat down.

The recruiter blinked, confused. Thought I was sick. I stood up, then sat again.

“I’m not moving,” I said, though I wasn’t sure I could if I wanted to. The sergeant’s face seemed to turn fire-engine red with anger.

My heart was a jackhammer. I was frozen in defiance—or maybe just fear. Either way, I wasn’t going forward.

Two MPs grabbed me like a sack of potatoes and hauled me to a holding cell. I was questioned by some army lawyer type who wanted me to be sure I knew what I was doing, and I asked him if he was sure if he knew what he was doing. Then came the police car, the ride to Staten Island, and my first night in jail. From the gridiron to the county jail—five miles apart, a lifetime between.

As I was carried out of Whitehall Station, I had started refusing to walk. Part of my plan was total non-cooperation. Mr. Jones stood on the grimy New York sidewalk. He smiled. Gave me a thumbs-up. And from between some cop’s gun holster and his arm, I flashed him a peace sign.

And just behind him, in the blur of sirens and sidewalk noise, I saw Archibald MacLeish.

Not in a coat closet this time—but strutting down the curb in his beret and red bandana, cane tapping a rhythm only I could hear. He paused, tipped his hat, and whispered, “Courage isn’t loud, Sandy. It’s the quiet refusal.”

Then he vanished into the crowd.

That image is etched deeper than any classroom memory.

Mr. Jones arranged to bail me out, or hoped I’d be released on my own recognizance. I was up the next morning with a trial date set. I ended up at his home for the rest of the day—resting, recovering, trying to make more sense of what had just happened. But more importantly, what would happen next?

To my mother, I was simply visiting Mr. Jones. I was old enough to say, “Don’t call my parents,” and the authorities obliged.

A trial date was set for April. The lead-up was a blur of paperwork, legal advice, and quiet panic. I walked the streets of Manhattan like a ghost, memorizing the cracks in the sidewalk, the rhythm of subway trains, the smell of roasted peanuts from corner carts—anything to anchor me. I had oddly always found the Financial District of Manhattan relaxing on a Sunday morning. The insanity of Wall Street gave way to peace and silence. I walked Wall Street a few times in those last days in New York, and of course, Times Square, the lights of Broadway were not going to shine on me, but they do shine inside of me in my heart and memory. Just as the beaches of Staten Island still call to me.. I didn’t know what I was looking for, only that it wasn’t in New York anymore.

I got a message to Emily at a Post Office Box in Alderson, and I asked if her mountain was still standing. In a week, she answered. She said yes, with directions at least for the ones that were for the roads.. So I packed up and headed south, winding through the back roads past Alderson, deep into the West Virginia woods. I wasn’t running. I was regrouping. The mountain had always been there—quiet, steady, like Emily herself. And in that silence, I could breathe again.

The last stretch to Emily’s cabin was a two-mile hike up a narrow trail—no road, no signs, just the hush of the woods and the crunch of my boots on leaves. Each step peeled away the noise of the city, the courtroom, the cell. I carried no map, but the mountain knew the way. By the time I reached the clearing, my breath had steadied, and something in me had begun to loosen.

The mountain didn’t ask for explanations. It didn’t care about draft classifications, courtroom dates, or the ache behind my eyes. It just stood there—solid, indifferent, eternal. Emily met me at the porch with a mug of hot cider and a silence that felt like a gift of grace. I sat down, let the steam rise, and listened to the wind move through the trees like a hymn. Somewhere in that hush, I heard the tap of a cane on stone. Archibald MacLeish, beret tilted just so, stepped out from behind an old oak tree and said, “You made it, Sandy. Not by marching, not by hiding—but by listening.” He tipped his hat, winked, and vanished again

And for the first time in months, that night I slept.

Leave a comment